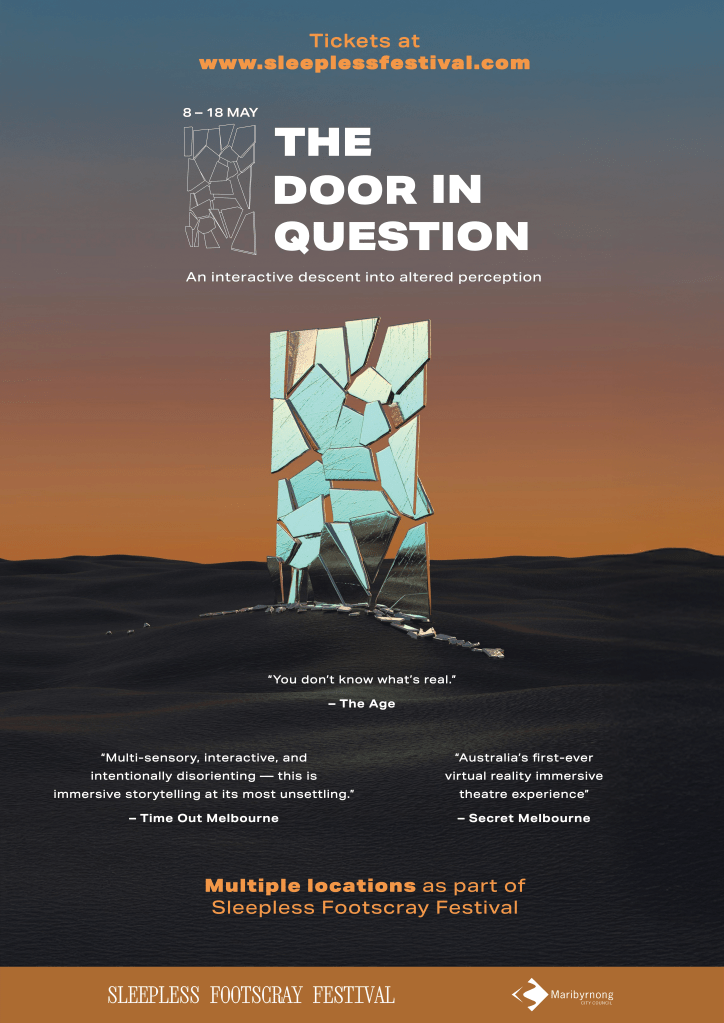

The Fame Reporter interviewed Troy Rainbow, Creative Director of The Door in Question, in Footscray as part of the SLEEPLESS FESTIVAL until 18 May.

For more information and to book visit sleeplessfestival.com

After-dark music and arts festival SLEEPLESS FESTIVAL is set to take over Melbourne’s inner west this May with a vibrant showcase of music, performance, art and installation.

From 2 to 18 May, Melbourne’s inner west will come alive after dark to celebrate the creativity and culture of its local artists. Now in its fourth year, Sleepless Footscray, supported by Maribyrnong City Council, will build on its success of previous years by staging art installations, film, performances, and immersive experiences in sixteen underutilised and unconventional Footscray CBD venues, highlighting the suburb’s potential as a thriving arts community with a vibrant nightlife.

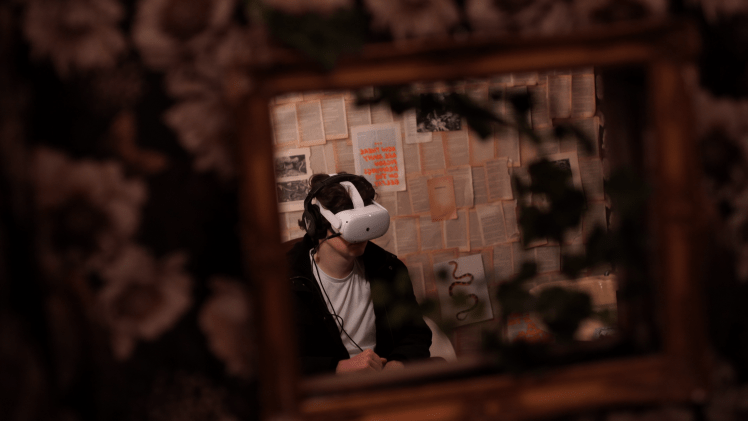

An exhilarating descent into altered perception, immersive theatre production THE DOOR IN QUESTION will illustrate the vivid experience of living with mental illness. Spaces will shift when you’re not looking and corridors will stretch in unfamiliar directions as reality shifts beneath your feet.

We had the thrilling opportunity to sit down with Troy and talk about his role in the creation of The Door in Question, how his personal experiences shaped the project and more.

The Door In Question is such a unique, deeply personal project. Can you tell us more about how your personal experiences shaped the creation of the show?

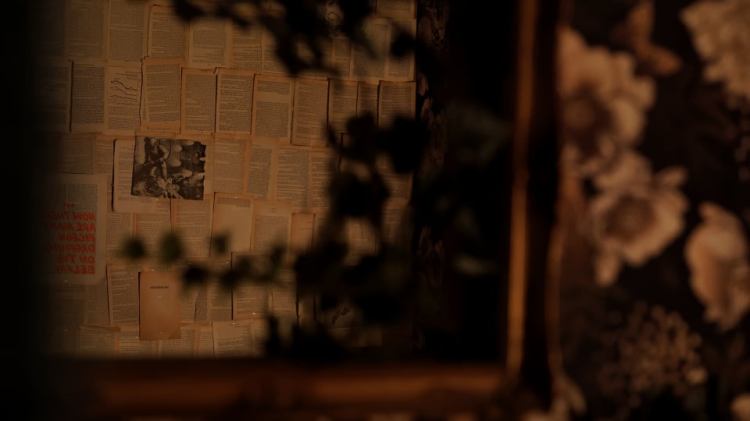

When my mother died, and I was cleaning her commission flat out with my brother and sister, we found piles and piles of her notes. I had all the letters and birthday cards, but these were different. It was a deep insight into her turmoil and suffering.

Yes, there were vitriolic complaints to institutions and threatening letters to family, but what was immediately evident was that she was acting from the pain of losing her first two children, and ultimately her third. It was heartbreaking to realise I hadn’t fully seen or understood that part of it.

Her prosody is fascinating, and her concepts and logic are completely inscrutable unless the reader understands her own experience. That’s what inspired me to do something with the notes I have, even if it took me several years to figure out what that would be. That’s also where the narrative part comes in.

She could mostly only manage to tell her story in a way that got people’s backs up, waving a white flag while doing circle work outside my sibling’s school, or telling people I was the product of an illegal artificial insemination conspiracy between her ex-husband and my father. All of it tangled with echolalia, fragmented references, distorted phrasing.

Psychosis for her wasn’t just confusion or hallucination. It was clarity. When you live near enough to it, you understand that just because something doesn’t sit in “consensus reality” doesn’t mean its emotional impact on someone isn’t just as powerful.

What was it like to translate something as complex and emotional as mental illness into a multi-sensory immersive theatre experience?

It’s hard to build something so emotionally raw without turning it into a spectacle. I didn’t want to make psychosis watchable, I wanted to show people the pathway to madness – the highlights and pitfalls of it; revelation, clarity; fear; paranoia; humour.

The only way to summarise an experience as deep as psychosis as an artist, is to try and hijack every element of a guest’s sensory environment.

Psychosis is insidious. It sneaks up on you. It tells you you’re amazing and the best thing in the world. Then, once it has you believing that, it strips away the cave walls and lets you crumble as you mediate with consensus reality.

How did your mother’s stories and gifts specifically influence the VR elements in the production?Mum’s storytelling was chaotic but vivid. Her birthday cards would start normal and spiral – literally spiral – off the page. Twenty extra notes folded up. Lists of which pigeons had been harmed. Who in the family was an alien.

Her gifts were piles of what looked like garbage – used dummies, salvaged objects. But they meant something to her. She was building a mythology from fragments, and I think VR works in a similar way. You construct meaning from layers that don’t always line up.

My mum once wrote me a children’s decodable reader and said, “I thought you might like to illustrate it.” So that’s what I’ve done. I’ve built her a world, using every strange detail I could remember. Something fractured, but full of love.

How do you balance depicting the disorienting aspects of psychosis without overwhelming or alienating the audience?

You don’t coddle them, but you don’t drop them off a cliff either. The piece builds slowly. You’re given instructions, but they’re a little off. You’re alone. No phones, no friends. There’s enough stillness and enough structure that people feel safe, but there are moments, glitches, contradictions, circular logic, that tilt the ground beneath them.

I want people to feel unsettled, not unsafe. The disorientation is carefully scaffolded. It’s not about shock: it’s about recognising yourself in something completely irrational. Which is terrifying in a quieter, longer-lasting way.

Can you speak more about the idea that “delusion and truth can exist inextricably” for people living with mental illness, and how this is represented in the show?

That’s the heart of it. People like to think of delusion as a glitch in perception, like a technical fault. But for the person experiencing it, it’s airtight. It makes sense within itself and inside that world, there’s love. There’s grief. There’s clarity, sometimes even revelation.

The show doesn’t “depict” delusion from the outside: it lets you believe in it. You’re told your breath controls the room. Or that you’re being watched. Or that you are the one doing the watching.

Some audiences walk away still not sure which parts were real. That’s the point. When you live with psychosis – or near it – the line between truth and delusion stops being linear. It curls in on itself.

Without giving too much away, what can audiences expect as they move through the multiple sites across Footscray?

Expect to be disoriented. You might start in one room and find yourself somewhere else entirely. Sometimes you’ll be followed. Sometimes you’ll be told you’re the one doing the following.

The abandoned shopping centre becomes a kind of transitional zone. One minute you’re holding your phone, the next you’re inside a cupboard full of wires, trying to make sense of something called “soul dust.” The environments change, but the feeling follows you.

It’s not a haunted house. It’s not a narrative game. It’s more like walking through someone’s decoded nervous system, and realising it echoes your own.

This is Australia’s first-ever VR immersive theatre experience — do you think XR technologies are the future of storytelling in theatre?

I think XR is less about the future and more about what’s possible now that wasn’t before.

Traditional theatre still has huge power, but XR lets you unhinge time and point of view. It allows you to place the audience inside the experience instead of observing it.

It’s particularly useful when dealing with mental states that don’t behave rationally. You can make a door lead somewhere impossible. You can make a voice come from inside the audience’s own skull. You can fracture the rules. And when the subject is madness, the form should be too.

Are there plans to take The Door In Question to other festivals or cities after Sleepless Footscray?Yes! We’re working on that now. The modular nature of the piece makes it adaptable to other disused spaces, and the response has been strong. It’ll need recalibration for each site, but that’s part of the fun. The dream is to let it live in different cities, with each version warped by the new space it haunts.

How do you see the role of independent festivals like Sleepless in supporting experimental and deeply personal work like yours?

Sleepless gave me permission to make something that doesn’t resolve cleanly. A lot of festivals need your work to explain itself. Sleepless didn’t.

They understood that deeply personal doesn’t mean small, and that experimental doesn’t mean inaccessible.

They let me build a world that was haunted, non-linear, uncommercial, and they gave it a home. That’s rare, and essential.

Word Play

VR headset or live stage?

Both

Footscray in one word?

Complex

Most unforgettable moment during production?

Threatening myself on an AI phone call.

Dream artist you’d love to collaborate with?

Wouter Kusters

One piece of advice you’d give your younger self?

Shut up

Strangest place you’ve found inspiration?

Medical Journals

A favourite memory linked to your mother’s creativity?

“The kids tell me you’ve been farting a lot and I told them that your mother farted a lot – and she got bowel cancer because of it.”

What’s harder: writing the story or building the tech?

The tech is embedded in the story. That’s how I write.

If The Door In Question were a song, what genre would it be?

Glitch IDM meditation fusion

First thing you’ll do after Sleepless Festival wraps?

Sleep… duh.

Most surreal audience reaction you’ve witnessed?

People not knowing how to use old phones!

One word you hope people use to describe The Door In Question?

Thought-provoking. That’s cheating, I know. But really, I hope they don’t talk and they just think and feel for a bit.

TICKETS

Playing until 18 May

All photos – Supplied